Sabrina Little on living 'The Examined Run'

My conversation with the ultrarunner, philosophy professor and new author on cultivating virtue + becoming who we are

Morning, friends! ☀️

Today’s issue is one I’m really excited to share with you, a conversation with one of my heroes in running: Sabrina Little, an assistant professor of philosophy at Virginia’s Christopher Newport University and a highly accomplished ultra runner who’s a former world silver medalist and a five-time U.S. national champion.

I’ve looked forward to talking with her ever since I discovered her column for IRunFar, which explores some of the same territory we cover here — how running shapes us, how we become who we are, and how our athletic pursuits can help us become better human beings.

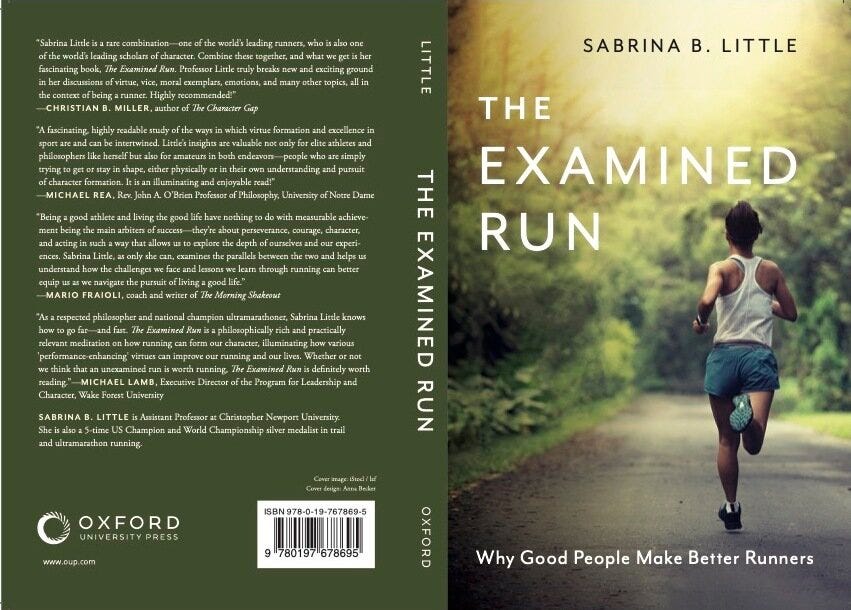

Her brand-new book, The Examined Run, digs deeper into all of this: how we choose the people we look up to, how athletic practice can reinforce the good things we want for ourselves, and how these fit into the kind of life we want to live. It’s a fascinating read, and one I really enjoyed. I hope you enjoy our conversation as much as I did! — Terrell

(And, if you’d like to see more pieces like this, help support THM with a paid subscription.)

TJ: Welcome, Sabrina! Your book is a fascinating tour of virtue as it relates to athletics, seen through the lens of a philosopher. (Which, of course, you are!) You've also been a competitive athlete from a young age, and have accomplished amazing things at a very high level in ultra running. I'd love to know, when did it strike you that there's a deeper, more philosophical side to running, that there is more to the sport than the obvious physical aspects of it?

SL: First, thanks so much for reading my book and asking such great questions. It is a special gift when someone reads your work with such thoughtfulness.

Philosophy begins in wonder. As runners, we spend time outside, often alone, and this affords us space to wonder about the world without being interrupted by phone calls and emails. This is a really special feature of the sport, and it is of increasing value in a world with so many digital distractions. We have the space to ask big questions about who we are and what we are doing here, as humans.

Wondering about the world, and systematically asking big questions, is also my task as a philosopher. So, pretty early on, I found value in that time spent running outdoors, removed from distractions, and able to think clearly.

I also found a special kinship between the work that I do in virtue ethics and in running. Virtues are acquired by practice. For example, we act courageously to develop courage, honestly to become honest, and so forth. In athletics, we have this same logic of 'practice.' We set out everyday in our sneakers to improve in certain respects — becoming faster, more courageous, more perseverant.

However, where character is concerned, if we are not intentional in our training, we may be developing the wrong things —imprudence, poor stewardship, intemperance, or impatience. These traits can impact our training, but also our lives outside of it. So, there is value in examining running as a formative practice. We should ask whether we are practicing being the kinds of people we want to be outside of the sport.

Can you talk a little about the title, The Examined Run? Readers of your column at IRunFar will likely be aware of what you write about, but for an audience who isn't, can you explain how you chose that title?

There is a famous line in Plato's Apology, that the unexamined life is not worth living. In that dialogue, Socrates is on trial for impiety and corrupting the youth . He has a bad reputation because he asks hard questions and is perceived as irreverent toward authority. He makes people angry. But Socrates believes he is doing a public service — demonstrating that the things they believe themselves to know, but do not actually know.

I share this objective with Socrates. It is part of my inheritance as a philosopher — being the person who asks hard (perhaps annoying) questions. I think it is important to self-examine and to prompt self-examination in others. In my column at iRunFar and in my book, I ask difficult questions of runners and running, so the title — The Examined Run — was a natural choice.

I'd also love to know, why this book at this particular moment? Is there anything about where we happen to be in our culture, and in sport, right now that prompted you to write the book?

Yes, there are a few reasons I felt compelled to write this book now. The first is a curiosity for the internal work that informs performance. Collectively, the running community is talking more about mental health and performance psychology as critical dimensions of peak competition. Issues of character are an important part of these conversations. For example, I cannot execute a race plan if I am impatient or lack courage. If I am envious of my competitors, this is going to shape how I show up in the community. We need to talk about character as part of these conversations.

I also noticed a pattern of moral inarticulacy, which is something I think extends beyond running. When “ethics” comes up in athletics, it often means someone has done something very wrong — doping or course-cutting. These conversations are often framed in terms of the negatives — what we ought not do. But we collectively seem to lack a vocabulary for discussing what we ought to do or be instead. So, part of the reason why I wrote this book was so that we could talk about what excellence is — what it might look like to have a good character and compete with excellence.

Finally, the sport is growing and changing considerably at the moment. This is awesome. It has been fun to experience growing enthusiasm and awareness of the sport. But with money and attention entering the sport, it is important to examine the ethos of ultrarunning — what has traditionally made it so special. Talking about character is a key part of these conversations.

Something that struck me as I read the book was the concept of eudaimonia, or the "good life" — meaning, a life of flourishing or living well, which seems to stand in contrast to pleasure-seeking, or satisfying desires and/or goals. Meaning, a good life is more than just satisfying one's desires — but, some readers might ask, what's wrong with setting a goal and going for it? What does eudaimonia offer that the way(s) we normally think about pursuing happiness don't?

Our intuitions about happiness are often wrong! This is not something unique to our culture or current moment. It's a human problem. We look to pleasure, money, fame, attention, power, beauty, and etc. to be happy, and these things cannot satisfy us. For example, you can pursue beauty, but beauty fades. If you seek money... well, money is not even an end in itself. It is a means to something else. These things don't make a human life a good one.

In The Examined Run, I assess two definitions of happiness that fail, before turning my attention to eudaimonia. The first is hedonism. This is the view that happy feelings make a happy life. This is shortsighted because some of the least smiley-face moments (having kids, running marathons, climbing mountains) provide the most meaning and purpose in our lives. Frowns are part of a rich human life. I think we tend to know that as runners.

A second candidate is goal-satisfaction — thinking that if we accomplish our objectives, we will be happy. But this is untrue. Say we finish a race and accomplish our wildest dreams (placing first, running a certain time, qualifying for the Olympics)... there is always life on the other side of that finish line. An example of this is the phenomenon of the "post-Olympic blues." People are not actually happier once they accomplish their greatest goals. Certainly, chasing goals is part of a good life, but it is an insufficient account of what makes a life a good one.

Eudaimonia is Aristotle's account. He defines it as an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue. It involves growing in excellence and not letting our capacities lie fallow. It takes seriously our human nature — the kind of thing a human is — that we are rational, social, and emotional. It involves seeing the world clearly, feeling the emotions we ought to feel, when we ought to feel them, and ordering ourselves toward good ends. There is space on this account to talk about suffering in a mature way.

In athletics, we often speak in all-or-nothing terms about suffering — “no pain, no gain” and “pain is weakness leaving the body.” But you can have serious questions about where suffering fits in, in a good life, on a eudaimonic account of happiness. Sometimes suffering edifies us… sometimes it's damaging. These considerations are invaluable for trying to figure out where athletics fits into a happy life.

As I read the book, I got the feeling that the things you're writing are very aligned with the season, or stage, of life you're in now — when you were younger and hadn't yet married or had children, you could devote much more of your time and identity to running. (And you achieved amazing things!) Now, of course, your life is different, and richer in so many ways; you're married, you have two young children, and a career as a professor that's fulfilling and demanding too. There is only so much time to run now, I imagine. How have you adapted to those shifts in your life, and what place does running hold for you now?

I want to believe that I would have written the same book at the height of my athletic powers, as I am now. But realistically, this stage of life (married, balancing two toddlers with work responsibilities and academic goals) has made salient the importance of having a long view of running. Running for peak performance can be myopic, or single-minded.

I think the book that I would have written in the past would have focused on some of the same ideas — e.g., striving with excellence and the importance of competing above reproach, in terms of honesty and integrity. But I think, in this new season of life, I have acquired a sensitivity to the many excellent ways we can inhabit the sport, because I have experienced the sport in different ways. I think this is a much better book than that one would have been.

Something I've dealt with at earlier points in my own life, and am dealing with now, are injuries that keep me from running the way I'd like to. You make a point in the book of how, especially when we're younger runners, we absorb the idea that our possibilities are limitless and we should always be seeking something greater — some greater achievement, some higher level, always more. But, from time to time, our bodies remind us that that isn't always possible — and, in some cases, it tells us we need to scale back our ambitions if we want to continue to do the thing we love, which is running. How do you think about that, in the context of the stage of life you're in and your own experience? How do you think about the concept of limits, especially in a world that encourages us not to?

Often in sports, we make bargains with our bodies for short-term gains, over long-term considerations. We may not be aware that we are even making these bargains. We run too many miles, or too many hard miles with insufficient rest or nutrition, or otherwise live unsustainably, without considering the long-term effects. This is especially common among ultrarunners, who sometimes have an intemperate love of movement. I think it is important to examine how the ways we occupy the sport now might inform our lives long-term.

One way to frame this discussion is to think about limits. We should think about the story of Icarus flying too high and melting his wings. He exceeded the bounds of safety.

Of course, we have physical limits — the maximal amount of work we can absorb. These limits shift throughout a season and year to year, as fitness waxes and wanes. We know we have exceeded our physical limits if we become overtired or injured.

Personally, I used to have exceedingly high limits. I could absorb a massive amount of training without the risk of injury. Over the past few years, since becoming a parent, my limits have lowered. I am not sleeping enough to absorb as much training! Now my proverbial Icarus wings melt at a lower altitude.

But there are also what Wendell Berry calls “cultural limits.” These limits include the people we love and responsibilities to neighbors. I don't know if this is true for everyone, but one of the first limits I am inclined to step over, when I mis-prioritize training, is time with family. We should not step over these limits either. In a full life, we have people we care for, who can count on us to be there.

One of things I love in the book is your discussion of exemplars, the heroes we choose, who represent the ideals we look up to and would like to emulate. It occurs to me that we need to be careful when we choose our heroes, because we tend to gravitate toward the things and people we admire — but also, “the heart wants what it wants,” if that makes sense. How do you think about the idea of choosing a hero or exemplar, in running or in any area of life?

Good question. Admiration is our guide for sure. It is a powerful emotion because it inclines us to imitate the excellences we see. For example, I notice the bravery of a track runner and I try to be likewise brave in my own race. But we need to critically reflect on the objects of our admiration to make sure they are worthy of our admiration, and we need to have a realistic view of what a human is — flawed, complex, unreliable, and probably not excellent in every way. Otherwise, admiration is a liability.

This is really important. To admire is not to deify someone, or put them on a pedestal. It's to see someone's excellences and acquire a vision for what a good life — in athletics or otherwise — might look like.

As far as who to select, running is full of excellent people! (Maybe I am biased.) To the extent that you are able, I would look for guidance from those who have been in the sport for a while (which indicates they are participating in a sustainable way) and have strong relationships with friends and family. This is a good indication that they compete in ways that do not undermine their communities.

Most readers of this newsletter probably fall into the category of "recreational runners," people for whom running is part of a happy, healthy life, and not necessarily a north star like I imagine it is for the more "hardcore" runner type. There's so much in your book that I think my readers can learn, but if one of my readers were to ask you, "what can I learn from this?" what would you say?

Too often we have a precise plan to develop our athletic abilities, and then we throw up our hands when it comes to moral character and hope for the best.

Developing a good character will not happen by accident. If you want to become more excellent in a given respect — more patient, more kind, more perseverant — you need to practice these traits until they define you in a stable way.

You can be a more excellent person, and it's on your initiative to become so. I hope that is the big takeaway.

And that’s our conversation! I want to thank Sabrina for taking the time to answer my questions so thoughtfully and thoroughly; it’s such a treat to have been able to have a conversation like this with someone who’s a hero both to me and, I’m sure, to many of you.

If you have questions for me or Sabrina, feel free to post them in the comments! And, as always, have a great run out there and keep in touch — and, keep me posted on how your running/life is going.

Your friend,

— Terrell

Not sure how this popped up on my feed but thanks for this interview. So cool to see what Sabrina is up to now. For a bit while she was in college, she lived a couple summers with me and a few roommates in Arlington VA. I credit her for eliminating music and headphones from my runs as she advocated running as a space to think and to find where our minds come to rest. Seems like she’s kept thinking very deeply and running very far.

Question for Sabrina. Will the book be available in audio format?