Over the past several weeks, I’ve been coaching my nine-year-old son’s youth basketball team. (Well, assistant coaching. But I’m there, helping out every practice and game!)

When you see them on the court — even when they’re horsing around, shooting baskets and grabbing rebounds in downtime during practice — the different skill levels of each of our players always catches my eye. For some on the team, like my son, this season is their first time ever dribbling a basketball; for others, they might as well be LeBron James or Stephen Curry out there.

It’s not lost on my son that he’s new at this, and that some of his teammates have years of playing already under their belts. I feel his hesitation when he gets the ball in a game, even though he already has learned how to rebound, how to dribble, how to take the ball down the court. But when there’s a chance to shoot a basket, almost always he passes the ball to one of the other players. He just doesn’t feel ready.

Basketball is a game that moves so fast. The players run quickly up and down the court, the ball shoots around through the air as the players pass it around, all while the sounds of the crowd carom off the walls and the floor, almost non-stop. Honestly, I don’t get how anyone ever learns this game — there’s so much sensory stimuli coming at you every second!

At our last game, though, my son did something he hadn’t until then — he took his first shot. In the middle of the scrum of players, our team’s and the opposing team’s, crowded around the basket, he looked up and finally tried for the basket.

I won’t keep you in suspense… it didn’t go in. But I was as proud of him for taking that shot as I was for one of our other players, who got somewhere in the neighborhood of thirty points all on his own. Because I knew what it took mentally for him to get to the point where he felt confident enough to try for a shot of his own, after watching his teammates do it game after game.

I know, because I felt that way too when I was his age. It was really hard for me to believe in myself, to the degree that I’d be willing to risk looking bad, like I didn’t know what I was doing, in front of a gym filled with parents and spectators. (It still is!)

Things like this wander through my mind when I run now, because a run is a time for thinking, isn’t it? About ourselves, the direction we’re heading, how we’re feeling, how our relationships are going — but also how the people we love are doing, where they’re going, what they need. Are they getting enough from us? Or too much?

When I look at my son, especially, I wonder to myself, how can I help him through this experience of growing into yourself? Last week, I wrote about what it feels like to be in the place Dante was in The Divine Comedy; now I wonder what it’s like to be Virgil, guiding someone through the challenges of life.

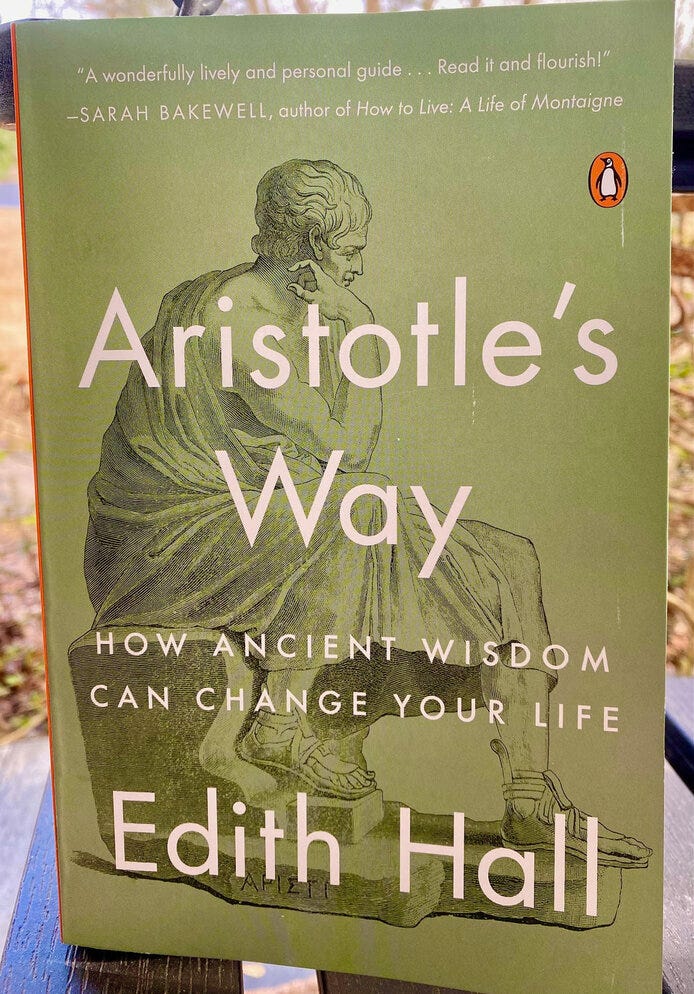

Lately, I’ve been reading a book that offers some interesting possible answers. I’ve been drawn to historical and philosophical books recently, like Sarah Bakewell’s How to Live on the life of the French essayist Montaigne, which I wrote about a few weeks ago. This new one — Aristotle’s Way, by Edith Hall — called to me from the shelves at Barnes & Noble, I’m convinced.

As the book begins, we meet the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle — about whose life we don’t know much, but do know that he lived between about 384 and 322 B.C.E., studied under Plato and founded his own school of philosophy, called the Lyceum, by about age 49. Between then and his death just over a dozen years later, he would write the treatises cited by countless writers and philosophers ever since, like the Nicomachean Ethics, Poetics and On the Soul.

Aristotle broke with his legendary teacher Plato in one primary respect, Hall tells us: rather than looking to general ideas around which to organize his life, or to the heavens above, Aristotle believed we should look more closely at our own lives — at what is right in front of us:

“Aristotle insists that creating happiness is not a matter of fanatically applying big rules and principles, but of engaging with the texture of life, in every situation, with every galloping horse, as we meet its particularity. There are general guides; just as in medicine or navigation, the doctor or the captain will be equipped with knowledge of certain principles, but every single patient and every single voyage will present slightly different problems, which call for different solutions.”

The book’s chapter titles hint at the story Hall wants to tell: “Happiness,” “Potential,” “Intentions,” “Self-knowledge,” “Communication,” etc. The overall arc, of course, is on how to live a happy, contented and fulfilled life — one marked by what Aristotle called eudaimonia, his word for happiness.

It’s worth pointing out that to Aristotle, eudaimonia isn’t something you feel — it’s something you do. It involves the pursuit of the good in life, and it asks something of us: that we cultivate the virtues needed to pursue it.

The way I’ve always understood that — cultivating virtue, or trying to make myself better — has brought to mind things like industriousness, persistence, discipline, focus… in other words, things that sound like a real chore. (Sure, I admire those things from a distance… but do I really want to try to be disciplined and focused with everything I do? Is that even possible?)

Aristotle would tell us that’s not the lesson we should draw, at all. Instead, we ought to pay close attention to what we take pleasure in — the activities that consume us, the subjects that absorb our attention — as a signal of the direction in which to point our lives.

For me, what I care about isn’t that my son become good at basketball. (Unless that’s what he wants.) I only want him to believe he can, and not to doubt that he’s capable of anything he wants to try. As Hall writes, this shouldn’t be hard for parents to do:

“Exposing your child to many different stimuli and activities, while watching out for signs of an enthusiastic response, is not so very difficult. But it is amazing how few parents help their progeny identify their natural talent.

Among my own circles of often hyper-educated friends and colleagues in the chattering classes there are far too many parents who impose their own vision of the ideal career or lifestyle on their children. One imagined, on zero evidence, that his three-year-old son was destined to become a world-class solo pianist (ten years later the son refused to ever practice the instrument again). What the boy actually liked doing, it seemed to me, was cooking, camping and orienteering. Another acquaintance ignored her daughter’s passion for engineering and forced her to take literary subjects at school and university; she has ended up bitter and frustrated, but at least she gets to fix things now that she’s become a plumber.”

That’s… exactly what I don’t want, of course!

It seems that introducing a child to a range of activities and interests, at levels that aren’t too difficult, is key. What’s interesting is, that works for exercise as well.

As I was writing this today, the latest issue of James Clear’s newsletter appeared in my inbox, with this quotation highlighted:

“Unfortunately, most on-ramps to exercise are at an intensity too high for previously-sedentary people to find them pleasurable. If people go to a fitness class, or focus on running a particular distance at a particular speed, they’ll likely miss the pleasure zone entirely.

Refocusing on exercising only for one’s own individual pleasure, as slowly as one prefers, and only at intensities that are pleasurable, is more likely to motivate repeat and habitual exercising. At that point, the enjoyment of exercise pleasure can build on itself, motivating longer and longer intervals of experiencing the pleasure.”

I hope I’m not connecting dots that aren’t actually there, but to me there’s a parallel between what Clear cites (from this article titled “Body Pleasure” by Sarah Perry) and what Aristotle gets at — we need to seek out activities that challenge us just enough, and not too much.

We’re surrounded by advertising that promotes running as something to be endured, something difficult and punishing — as a kind of penitence. But maybe… that doesn’t work? For most people, anyway.

Perry asks us to turn things around and look at exercise in the way Aristotle might ask us to, I think:

“If you believe that exercise is ‘moral’ in some sense — good for mental health or weight loss, perhaps — you may be better off forgetting what you think you know, and pursuing exercise only for the way it makes your body feel.”

Those sound like wise words to me 😉

As always, I hope you’ve had a great week so far! Keep in touch and let me know how your running/life is going — especially if you’re training for a race this spring!

Your friend,

— Terrell

"Happiness is not something you feel, it is something you do." - This is the takeaway for me in an essay full thoughts that will keep me pondering. Great essay, Terrell and I admire your reading list!!!

Neither one of my sons was very athletic at a young age. One liked to draw, like his father, and the other liked books. When my oldest wanted to try Karate, I joined with him. It was something we could do together. He stuck with it for almost two years before he grew tired of the tough workouts. I never pressured him to continue. When I started something as a child, my father NEVER let me quit. If it's not fun, they'll eventually get bored. Even as an adult, I like to try different things. Some I've stuck with, but others went by the wayside. I continue with my two loves, running and writing, and never plan to stop.