I’d like you to take a good, long look at this painting, in which George Washington and three dozen or so of the convention delegates attend the signing of the U.S. Constitution in 1787. Keeping in mind, of course, this is an artist’s interpretation — it was painted about 150 years after the events it depicts, by artist Howard Chandler Christy — we can be reasonably certain this was how these men dressed, behaved, and otherwise comported themselves.

Notice their hair; most are wearing powdered wigs, while some wear ribbons and bows. Notice the frilly, puffy shirts, and what appear to be lacy cuffs sticking out of the ends of their coat sleeves. We can’t see most of their legs, but they’re probably all wearing the same kind of stockings we see Benjamin Franklin wearing in the foreground.

And if you can recall it from your high school or college history class, take a look back at the way they spoke to each other, especially in the letters they wrote one another regularly over the course of their lives.

I can’t remember the first time I read or heard about them — probably in Ken Burns’s documentary on Thomas Jefferson — but I’ve always been struck by the correspondence between Jefferson and John Adams, both former presidents and founding fathers looking back on their lives.

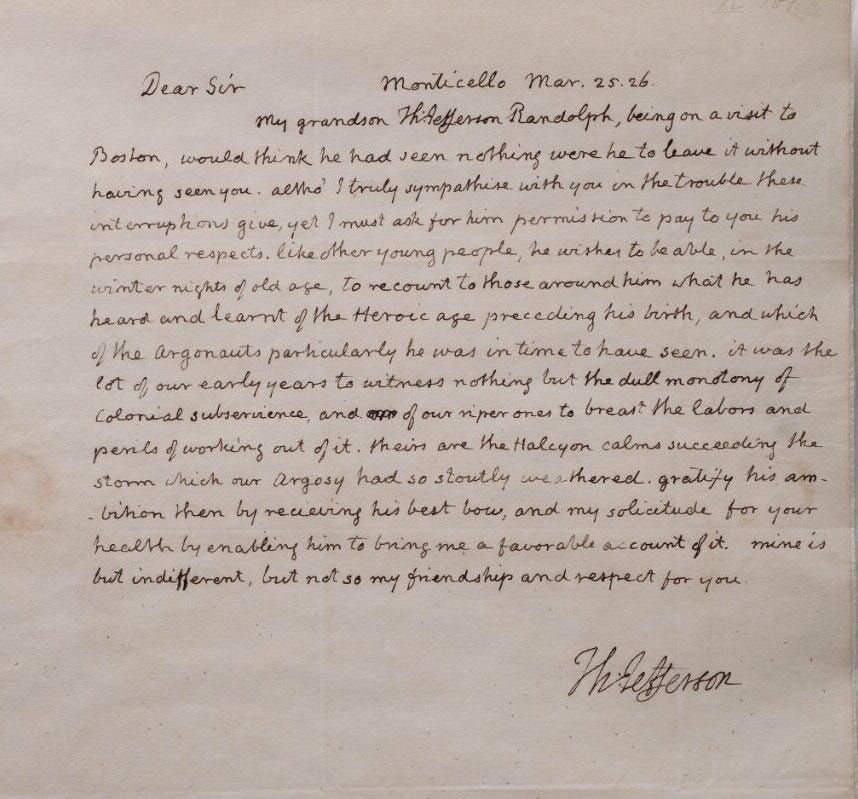

Look at this one, written by Jefferson to Adams just a few months before they both died (on the same day, in fact: July 4, 1826). They had left their bitter rivalry behind and rekindled a friendship that began in the early 1780s, when both were appointed as ministers to France.

I’ll spare you the history lesson, because what I really want you to see are Jefferson’s words to Adams — the kinds of words they wrote in hundreds of letters to each other over the last dozen years of their lives:

Writing about his grandson’s visit to Adams’s home in Boston, Jefferson says he “would think he had seen nothing were he to leave it without having seen you.” And in closing the letter, he writes that he hopes his grandson communicates “my solicitude for your health by enabling him to bring me a favorable account of it. Mine is but indifferent, but not so my friendship and respect for you.”

I share this with you not because it was out of the ordinary for Jefferson’s and Adams’s time — but rather because it was completely ordinary. Their letters are filled with the most flowery, moving, expressive, and poignant sentiments, ones we hardly can imagine now.

The way men spoke to one another, the affection they professed, the emotions they expressed, all were unremarkable for their day and time. (And yes, I know, they also had an honor culture and engaged in duels… but let’s leave that aside for now.)

You may, of course, be asking yourself… why am I reading about interpersonal relationships among men in the 18th century? It’s something that pops into my mind whenever I read about the epidemic of loneliness so many people today experience, who think they can’t reach out and let someone else know how they’re feeling. And because I am one, I know how this affects men all too well.

Today, as I write these words to you, my daughter is home from college to attend the funeral of a friend she graduated high school with, a friend who died by suicide last week.

He was 19 years old. (I’m not even sure whether to call him a “boy” or a “young man” at that age.) He left no note, gave no one any signs of his intentions. My daughter tells me he always brought everyone’s spirits up, that he was always filled with laughter, and always could see the brighter side.

To say that she and everyone she knows are in shock is an obvious understatement. We’ve been talking about it for days here in our house, trying to understand what happened, why it happened. We’ll never know, but clearly he carried something around with him, for who knows how long, that he felt he couldn’t verbalize.

It’s that last point that burrows down deep inside, that won’t let go. Whatever was bothering him, he felt he couldn’t talk about it — a feeling that, tragically, is all too common.

And I know it too. I was born in the 70s and grew up in the 80s, so I know very well the kind of culture most American men are born into. Whatever difficult emotion you’re feeling, you might be able to share it with a girlfriend or, if you’re lucky, a very close friend; but it’s better not to share it with anyone at all. And outside that tiny circle, only one emotion is okay for you to express outwardly: anger. Never sadness, never shame. Feeling down? Feeling vulnerable? Well, then you need to suck it up.

The truth is, no one ever sits you down and tells you this. No one spells out “this is how you need to behave, and what you can and can’t say, think or feel” when you’re growing up. But it’s undeniably there, in the water we swim in, in the air we breathe. I don’t know how we get the message, but sooner or later we always do — loud and clear.

What’s crazy to me — and the reason I started this essay with what a “real man” looked like back in the 18th century — is that it hasn’t always been this way. Today’s hard, stoic masculine ideal would be seen as laughably, ridiculously constricting and suffocating by our 18th-century forebears (if it weren’t so clearly sad and tragic).

Look at the clothes they wore, the social play they engaged in, the expressiveness in the way they spoke to one another — a cultural norm, I might add, that continued into the 19th century, which we can see in the letters Abraham Lincoln (and many others) exchanged with close friends.

Somehow, somewhere along the way, our culture gave up on this. I don’t know exactly when, or exactly why. But it did. And today we feel the impact.

I don’t know how to change this, or where even to begin. I just know that we have to. Because what we’re doing, the direction the culture lays out for boys and young men right now, is not working.

All I can do is try with my son, who recently turned ten. He’s talkative and shares everything he’s thinking and feeling — my job now is to make sure he stays that way as much as possible.

I’d love to know what you think, how you feel — and, as always, keep in touch and let me know how your running/life is going.

Your friend,

— Terrell

Thank you. Perhaps the best thing a man can do, in this area, is not to look for someone that he can safely talk to but to become someone that others can safely talk to. More so to actually encourage men around us to talk to us and for us to just listen while avoiding trying to fix stuff. I am thankful that I have friends in my life that i completely trust. They truly care about me. I think they feel the same about me. They know I love them and that I am there for them. It has added so much more meaning to my life. I am grateful

I’m so sorry for what your family is going through. Your perspective here is so valuable. I’m also a child of the 70s/80s, “effortlessly stoic”, and generally upbeat. I hope I’m not being an unrealistic role model for my two sons…