After all these years, I can’t believe we’ve never talked about Unbroken.

I was looking through our newsletter archives this week, certain that I’d written about it before. But apparently I was wrong.

If you’re not familiar with what I’m talking about, Laura Hillenbrand’s 2010 book tells the story of the Olympic distance-runner-turned-war-hero Louis Zamperini, a bombardier in World War II who survived a plane crash in the Pacific Ocean — on a raft, for 47 days — before being captured by the Japanese, enduring more than two and a half years as a prisoner of war.

His story is the stuff of legend now (and a 2014 movie directed by Angelina Jolie); during his time as a prisoner, he suffered almost unimaginable brutality at the hands of his captors. A year after his release, he married and had two children with his wife Cynthia, but struggled for years with post-traumatic stress, with which he attempted to cope by heavy drinking.

It wasn’t until he decided — after several years of drunken escapades piling up, adding to the ledger of his pain — to forgive and let go of what had happened during the war, that he was able to truly live again.

All of that is fascinating, and an amazing story that Hillenbrand tells in a much more captivating way than I can. But it’s not what interests me the most about Zamperini’s story.

What draws me in even more is where his story begins, in the 1920s as a kid on the streets of Torrance, Calif. It’s there that the Louis who would survive those 47 days floating on the Pacific, who would become an Olympic distance runner — and compete in the 1936 summer games in Berlin — was formed. Only he didn’t start out so impressive.

My wife and I were talking this past weekend about our 8-year-old son’s behavior. That we’ve been worried about how mischievous he’s become lately, how he doesn’t seem to care about parts of his schoolwork, or the way he acts around adults, etc.

Then I remembered what Louis was like as a grade schooler, according to Hillenbrand:

… at the Gramercy Avenue house where they settled a year later, [Louis’s mother] Louise kept prowlers out, but couldn’t keep Louie in hand. Contesting a footrace across a busy highway, he just missed getting broadsided by a jalopy. At five, he started smoking, picking up discarded cigarette butts while walking to kindergarten. He began drinking one night when he was eight; he hid under the dinner table, snatched glasses of wine, drank them all dry, staggered outside, and fell into a rosebush.

On one day, Louise discovered that Louie had impaled his leg on a bamboo beam; on another, she had to ask a neighbor to sew Louie’s severed toe back on. When Louie came home drenched in oil after scaling an oil rig, diving into a sump well, and nearly drowning, it took a gallon of turpentine and a lot of scrubbing before [his father] Anthony recognized his son again.

Thrilled by the crashing of boundaries, Louie was untamable. As he grew into his uncommonly clever mind, mere feats of daring were no longer satisfying. In Torrance, a one-boy insurgency was born.

Some of the details Hillenbrand includes are charming; you catch yourself laughing as you read her retelling of Louie’s skulking around town to find trouble: “Housewives who stepped from their kitchens would return to find that their suppers had disappeared. Residents looking out their back windows might catch a glimpse of a long-legged boy dashing down the alley, a whole cake balanced in his hands.”

As Louie got older, however, things changed. What seemed mischievously charming at age 9 has begun to feel dangerous by the time he reaches his teenage years:

Over time, Louie’s temper grew wilder, his fuse shorter, his skills sharper. He socked a girl. He pushed a teacher. He pelted a policeman with rotten tomatoes. Kids who crossed him wound up with fat lips, and bullies learned to give him a wide berth…

Anthony Zamperini was at his wits’ end. The police always seemed to be on the front porch, trying to talk sense into Louie. There were neighbors to be apologized to and damages to be compensated for with money that Anthony couldn’t spare.

At age 15, Louie decided he’d had enough of school and especially of the track team his brother Pete had persuaded him to join. He hated the discipline of training every day, even though he won many of his races. He hitchhiked to nearby Los Angeles with a friend, but several days of getting chased off trains and out of grocery stores for trying to steal food left the pair “filthy, bruised, sunburned, and wet, sharing a stolen can of beans.”

That turned out to be Louie’s last straw. He headed home and rededicated himself to the life he’d left behind — and jumped back into running. With the school year over, he spent the summer running practically all day long, to get ready for his high school track team’s upcoming year:

In the summer of 1932, Louie did almost nothing but run. On the invitation of a friend, he went to stay at a cabin in the Cahuilla Indian Reservation, in southern California’s high desert. Each morning, he rose with the sun, picked up his rifle, and jogged into the sagebrush. He ran up and down hills, over the desert, through gullies. He chased bands of horses, darting into the swirling herds and trying in vain to snatch a fistful of mane and swing aboard. He swam in a sulfur spring, watched over by Cahuilla women scrubbing clothes on the rocks, and stretched out to dry himself in the sun. On his run back to the cabin each afternoon, he shot a rabbit for supper. Each evening, he climbed atop the cabin and lay back, reading Zane Grey novels. When the sun sank and the words faded, he gazed over the landscape, moved by its beauty, watching it slip from gray to purple before darkness blended land and sky. In the morning he rose to run again. He didn’t run from something or to something, not for anyone or in spite of anyone; he ran because it was what his body wished to do. The restiveness, the self-consciousness, and the need to oppose disappeared. All he felt was peace.

I’ve emphasized those last two sentences because they reveal a deep truth, I think. When we stop and listen, and be still, we can hear answers that otherwise elude us. Look, I know it took more than simply running those hills during the summer of 1932 for Louie to experience his epiphany. But I’m not sure he would have experienced it without all that running, either.

I say that also because, if you’ve been following the training plan that many of us have been running since the start of the year, we’re coming close to the conclusion — when we finally scale that mountain and run 13.1 miles.

The temptation now, of course, is to let up. You’ve run all these miles, you’ve built up all this fitness. Why not simply coast through the final couple of weeks? (Believe me, I know — I’ve given in to this temptation in the past!)

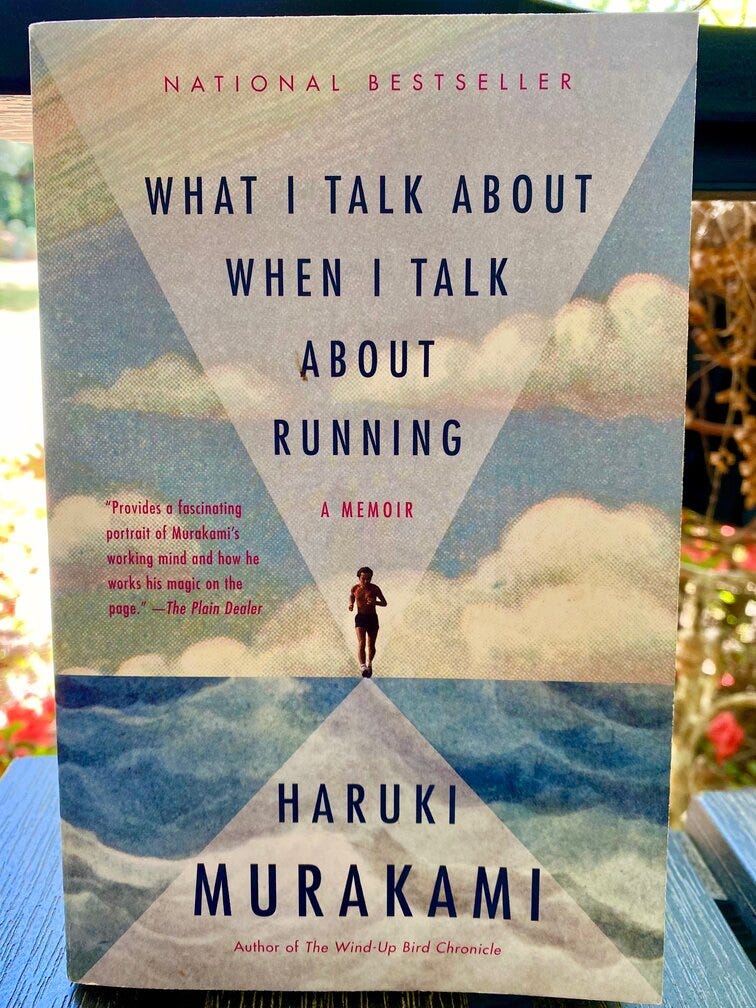

However, there’s just a little bit further to go. The famed novelist Haruki Murakami wrote about this beautifully in his 2007 memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, in which he shares exactly what it’s like to experience this part of training:

In the three months up till now I was basically trying to rack up the distance, not worrying about anything, but steadily increasing my pace and running as hard as I could. And this helped me build up my overall strength: I got more stamina, built up my muscles, spurred myself on both physically and mentally. The most important task here was to let my body know in no uncertain terms that running this hard is just par for the course. When I say letting it know in no uncertain terms I’m speaking figuratively, of course. No matter how much you might command your body to perform, don’t count on it to immediately obey. The body is an extremely practical system. You have to let it experience intermittent pain over time, then the body will get the point. As a result, it will willingly accept (or maybe not) the increased amount of exercise it’s made to do. After this, you very gradually increase the upper limit of the amount of exercise you do. Doing it gradually is important so you don’t burn out.

Once you get to the later stages, he adds, you can make the shift from quantity to the quality of the miles you run:

The total amount of running I’m doing might be going down, but at least I’m following one of my basic rules for training: I never take two days off in a row. Muscles are like work animals that are quick on the uptake. If you carefully increase the load, step by step, they learn to take it. As long as you explain your expectations to them by actually showing them examples of the amount of work they have to endure, your muscles will comply and gradually get stronger…

If, however, the load halts for a few days, the muscles automatically assume they don’t have to work that hard anymore, and they lower their limits. Muscles really are like animals, and they want to take it as easy as possible; if pressure isn’t applied to them, they relax and cancel out the memory of all that hard work. Input this canceled memory once again, and you have to repeat the whole journey from the very beginning.

But that’s not gonna happen for us, right? Because we’ve made it this far, and we have only a couple more weeks to go. There are many reasons you could have quit by now, but you haven’t — you’ve found the ones you need to keep going.

In other words, you’ve given yourself the kind of experience that makes you say to yourself, “I can’t believe I just did that.”

Have an awesome, awesome run out there today — and as always, keep in touch and let me know how it goes.

Your friend,

— Terrell

Our training plan for this week

It wasn’t until I’d already sent out last week’s issue that I realized I made a mistake. There are only two weeks left before we’re set to run 13.1 miles, which means we need at least a weekend without a big, long run like we’ve been running.

So, this weekend, feel free to run either 11 or 12 miles as your long run — if you’re feeling spry, why not try 12? If not, eleven will be fine:

Thursday, April 21 — 4-5 miles/40-50 minutes

Saturday, April 23 — 11 miles/110 minutes or 12 miles/120 minutes

Sunday, April 24 — 2 miles/20 minutes

Tuesday, April 26 — 5-6 miles/50-60 minutes

Let me know how it’s going for you and if you have any questions about the plan, your running, or anything else 👍

Discount for the Madison Marathon

Our friends at Wisconsin’s Madison Marathon shared with me a race discount code they’ve created just for subscribers to The Half Marathoner!

Use the code Half15 to save $15 off the:

Run Madtown Half Marathon on May 29, 2022

Madison Marathon & Half Marathon on November 13, 2022

Great input. I just finished a half marathon last weekend and have another to do on May 1st. I agree with Murakami...keep in training without taking two days off in a row, even if you run a few miles...."muscles are like work animals." The "half" last weekend was like a mud run given the torrential downpour and running along trails through woody areas but because of steady training, I ended strong. Much better than I anticipated and when I crossed the finish line, I could have kept going!

Hi Terrell. I love this article. As a Mom, I was in sympathy for Zamparini's Mom. I wanted to share that our training group did a particularly hard hill repeat series two Wednesdays in a row- in different locations- both equally hard. Our coach was so proud of the effort we all put in and he encouraged us to write a note or write on our bathroom mirror "I did that hard thing!". He wanted us to wake up to it the next day feel good about the work. I left mine up all week! Celebrating the hard things makes doing the next hard thing feel not so hard!