It’s very easy, in the era we live in, to get caught up in the quantified self. To get lost in the data our smartwatches and phones generate about our bodies on a moment-by-moment basis throughout the day — and even during the night, if you wear a watch to monitor your sleep.

Of course, I’m not immune to this temptation. I wear an Apple Watch and find myself checking it at the oddest times; for some reason, I’m always curious what my heart rate is and how it compares to what it should be for someone my age. (I even give myself a little mental high-five when it falls within shouting distance of the “athlete” range, however fleeting those moments might be.)

But all of that data can give us a false sense of mastery over our physical selves. The digits we see on the screen, highlighting how many steps we’ve taken or how many minutes we’ve exercised, can give us the impression that we know what’s going on in our bodies to a much greater degree than we actually do.

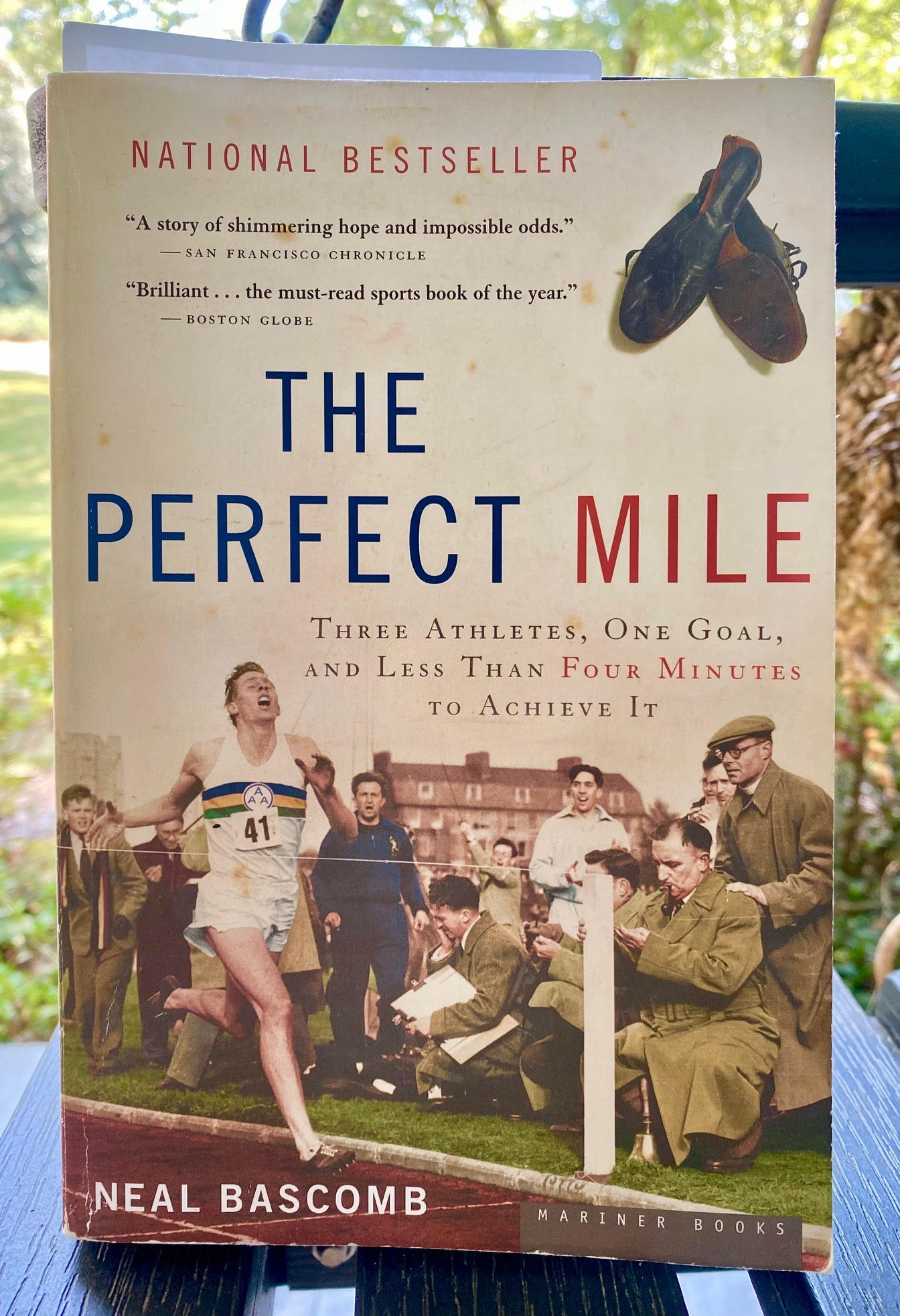

I’ve been thinking about this as I read The Perfect Mile, a book written almost 20 years ago by bestselling author Neal Bascomb (who also writes an amazing newsletter you should check out) about the quest to break the four-minute mile, pursued by three now-legendary runners back in the early 1950s.

Their names were Roger Bannister, John Landy and Wes Santee — an Englishman, an Australian and an American — and all had gained fame in their respective home countries as the runners to beat in track and field at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki, only to meet with miserably disappointing defeat in their events.

Bannister especially felt dejected over his failure to medal, for which the British press subjected him to withering criticism, splashing headlines like “Bannister Fails!” across their front pages. (Had he not failed so spectacularly, though, he may never have found the motivation to go after the four-minute mile.)

What really interests me about their stories are the details Bascomb shares about how they trained, and how they built themselves into the runners they became. You might think that because they’re Olympians, they must have known what they were doing.

Not exactly.

To qualify for the Australian Olympic team, Landy worked with a coach named Percy Cerutty, who had him undergo training exercises that today we’d find… unconventional:

In the year since Landy had first called on Cerutty he had paid close attention to the coach’s direction. He had paid ten shillings for lessons on how to move his arms and how to run like a rooster, clawing at the air. He had strengthened his upper body by lifting dumbbells. He had participated in running sessions on a two-and-a-half-mile horse path … and he had bounded up and down Anderson Street Hill with the others under Cerutty’s watchful eye. Their runs provoked gasps from the Melbourne residents nearby. They couldn’t understand what these young men, hounded by a shirtless older man, were doing. Running for exercise was odd in and of itself, but a group doing so through the botanical gardens carrying bamboo poles in each arm and shrieking like banshees as Cerutty called to them like “primitive man” was pure scandal.

As crazy as that sounds, it was nothing compared to the punishments Bannister put his body through (as well as a few of his friends, whom he recruited to test the limits of endurance in the laboratory).

When he trained for the Olympics — and after, as he trained in pursuit of the four-minute barrier — Bannister was a full-time medical student at Imperial College London. That meant he was usually limited to a single, 45-minute training session in a day packed with classes, rounds at the hospital and the socializing expected of someone of his station.

He was fascinated by the human body’s limits, and sought to find them in order to figure out how he could maximize his physical powers:

This understanding of what was known and what was unknown came at the expense of a lot of sweat, and blood, from Bannister himself and his test subjects — or guinea pigs, as Norris McWhorter referred to them.

“Do you think you could come along and help me with an experiment?” Bannister had asked. Without much reflection or investigation, McWhorter had replied, “Oh, yes.”

McWhorter found himself in a small room crowded with a motorized treadmill and a frightening array of attachments: gas bags, meters, valves, pipes, tubes, and pumps. It looked thrown together on a tight budget and a prayer. The door closed swiftly behind him. Stripped down to a pair of shorts and running shoes, McWhorter winced as the assistant took his hand and shot a spring gun attached to a scalpel blade into his finger to draw blood. His singlet was already stained with blood before the experiment began. He stepped onto the treadmill and secured his mouth around a rubberized tube that jutted out over the front of the adjustable platform. From what he understood, the experiment measured the effects that different oxygen mixes (from a normal level of 21 percent to as much as 75 percent) have on the body when running to exhaustion. By using the mouthpiece, he inhaled enriched air. His exhalation was then measured for a variety of factors too complicated to explain to every guinea pig.

Of course, this is cutting-edge modern science compared to the athletic traditions handed down to us from the ancient Greeks and Romans, who had some very interesting ideas about how to train: the Greeks “skipped, jogged, hopped, and, on occasion, sprinted while rolling a large hoop in front of them,” as “their coaches carried forked sticks for motivating them.”

Milo of Croton is said to have “walked every day with a calf in his arms in order to gain strength in his arms and legs slowly as the cow matured,” while the Romans familiarized themselves with pain by having slaves flog their backs with rhododendron branches until they bled. And as late as the 17th century, Bascomb writes, athletes were having their spleens removed because it was believed to make them faster.

I share all of that because there’s another story that I’ve been in love with for a long time, one I return to often: Laura Hillenbrand’s Seabiscuit, about the Depression-era thoroughbred horse who captured the nation’s imagination like no other athlete of the time, as described in the book’s opening pages:

When he raced, his fans choked local roads, poured out of special cross-country “Seabiscuit Limited” trains, packed the hotels, and cleaned out the restaurants. They tucked their Roosevelt dollars into Seabiscuit wallets, bought Seabiscuit hats on Fifth Avenue, played at least nine parlor games bearing his image. Tuning in to radio broadcasts of his races was a weekend ritual across the country, drawing as many as forty million listeners.

As a young one- and two-year-old horse, however, Seabiscuit showed none of this promise. He was seen as lazy and indolent — thanks to his preference for sleeping and lazing about in his stall for hours on end — and he was whipped constantly and ridden hard, almost always to the point of exhaustion.

But none of this worked. It only made him harder for humans to ride him, to the degree that no jockey dared go near him.

It wasn’t until he was sold to a new owner, who hired a trainer named Tom Smith with an entirely different philosophy about how to treat horses, that Seabiscuit began to grow into his potential.

Smith refused to treat him with anything but the gentlest touch. He placed animals in his stall as a comfort, and saw to it that he had only the best food to eat. He gave him time to detach from the trauma he’d experienced, or so Smith thought:

Once Seabiscuit was settled in Detroit, Smith took the colt to the track to stretch his legs. It was a disaster. Seabiscuit didn’t run, he rampaged. When the rider asked him for speed, the horse slowed down. When he tried to rein him in, the horse bolted, thrashing around like a hooked marlin. Asked to go left, he’d dodge right; tugged right, he’d dart left. The beleaguered rider could do no better than cling to the horse’s neck for dear life. Smith watched, his eyes following the colt as he careened across the track, running as a moth flies.

Smith knew what he was seeing. Seabiscuit’s competitive instincts had been turned backward. Instead of directing his efforts against his opponents, he was directing them against the handlers who tried to force him to run. He habitually met every command with resistance. He was feeding off the fight, gaining satisfaction from the distress and rage of the man on his back. Smith knew how to stop it. He had to take coercion out of the equation and let the horse discover the pleasure of speed. He called out to the rider: let him go.

The rider did as told, and Seabiscuit took off with him, trying once to hurdle the infield fence but meeting with no resistance from the reins. He made a complete circuit at top speed, but Smith issued no orders to stop him, so around he went again, dipping and swerving.

After galloping all-out for two miles, weaving all over the track, Seabiscuit was exhausted. He stopped himself and stood on the track, panting. The rider simply sat there, letting him choose what to do. There was nowhere to go but home. Seabiscuit turned and walked back to the barn of his own volition. Neither Smith nor his exercise rider had raised a hand to him, but the colt had learned the lesson that would transform him from a rogue to a pliant, happy horse: He would never again be forced to do what he didn’t want to do. He never again fought a rider.

Why are both of these books commingling in my mind right now? There’s something each gets at that is essential about running to me. Of course we need to be disciplined when we set out to train for something like a half or a marathon; we’d never make it 13.1 or 26.2 miles without it.

But if we let the joy leach out of it, we’re in for nothing but a long slog. That means (to me, anyway) that we can’t let the “pleasure of speed” be far from our minds — that, like Seabiscuit, we have to be willing to let go of the reins sometimes, forget our plan and just let ourselves run free.

Despite how sophisticated we imagine ourselves to be today, with devices on our wrists and in our pockets that quantify everything physical about us, what makes this worthwhile is the feeling we experience when we do it — and there’s something magical about that, that no device can quantify.

I hope you’ve had a great week so far and are getting some great runs in — as always, keep in touch and let me know how things are going.

Your friend,

— Terrell

P.S.: Neal and I spoke earlier this week for a video interview, which I plan to share with you on Friday 👍

Our training miles for this week

How did your 19 miles go last week, if you’re training with the 12-week plan we’ve been laying out? Or your 16 miles, if you’re progressing with the 4-month plan? (Or your 14 miles, if — like me — you’re training for the 10-miler?)

I’d love to hear how it’s going for you. Here are our miles for the upcoming week:

For the 12-week plan:

Thursday, Sept. 22 — 3 miles/30-35 minutes

Saturday, Sept. 24 — 6 miles/60-65 minutes

Sunday, Sept. 25 — 4 miles/40-45 minutes

Tuesday, Sept. 27 — 4 miles/40-45 minutes

Wednesday, Sept. 28 — 5 miles/50-55 minutes

The 16-week plan:

Thursday, Sept. 22 — 3 miles/30-35 minutes

Saturday, Sept. 24 — 6 miles/60-65 minutes

Sunday, Sept. 25 — 3 miles/30-35 minutes

Tuesday, Sept. 27 — 4 miles/40-45 minutes

Wednesday, Sept. 28 — off

The 10-mile training plan:

Thursday, Sept. 22 — 3 miles/30-35 minutes

Saturday, Sept. 24 — 5 miles/50-55 minutes

Sunday, Sept. 25 — 3 miles/30-35 minutes

Tuesday, Sept. 27 — 4 miles/40-45 minutes

Wednesday, Sept. 28 — off

Let me know how it goes, and don’t hesitate to reach out! — Terrell

Thanks for the wonderful piece on Perfect Mile. Authors aren’t supposed to have favorite books, but between us, this is in my top 3. I never made that connection with Seabiscuit, particularly the drawing back from training to enjoy the pleasure of speed. Bannister’s coach Franz Stampfl did the same thing with Roger shortly before he broke four-minutes. In his case, an adventure in Scotland to free his mind.

Terrell, I love the way you connect the dots so that 1+1=3. Powerful and compelling and demonstrates your “intuitive ability” to trust yourself and see the bigger picture. You will soon discover “less is more” when you wean yourself from all that distracting technology. Your body clock knows what time it is and your heart knows what is necessary and what is not. You are clearly on your way to “Know Thyself” an imperative modern man truly doesn’t get....I apologize for the unsolicited advice.