Right around this time of year almost a decade ago, I got a phone call from my mom with a question that immediately piqued my interest:

“Want to go with me to Cuba?”

Well of course I did, but my wife Meredith and I had a 12-year-old and two-year-old at home, and I had to work, and this, and that, and well…

“When do we go?”

In a few months, she said. The trip would be in mid-March.

Well, I thought to myself, when will I get a chance to travel to Cuba again? I knew it would be a stretch to make it work with the rest of my life, but… I said, “of course, I’ll go.”

And, fast-forward three months, we’re on a plane from Miami making our way over the Straits of Florida on our way to Havana, where we’d land and spend the next week with a tour group, seeing the city as well as the farming region known as Pinar del Río, on the western tip of the island.

Once we landed, spent the night at our hotel and got our bearings, we went off into the city, exploring.

We walked through plazas like the one in the photo above; we walked along the Malecón, a five-mile promenade perched atop a seawall, where Havana’s young people rendezvous at night.

The architecture of the buildings looked as if they had once been beautiful, majestic even. It’s a cliché, but they really did have “good bones,” even if many of them were more or less crumbling.

You probably know the reasons why. The longstanding U.S. embargo plus a legacy of reliance on the former Soviet Union and a still-centrally planned economy have left this once-popular tourist destination enfeebled; one man I met, who shared how low most Cubans’ incomes were, said simply, “we find ways to get by.”

Not everyone we met had a sad story — not by a long shot. I’m sure I’m far from the only one to experience this, but to a person, everyone we met in Cuba was warm, friendly and welcoming. They were open, they spoke honestly about what life there was like.

It was hard, I learned. For starters, at the time there was no island-wide internet service; in Havana, people crowded around the outside of a baseball stadium we drove past, sitting on the sidewalks while catching up on their text messages via the stadium’s wi-fi.

Out in the Pinar del Río countryside, we met a tobacco farmer named Benito who made fun of us being so attached to our cell phones; to show us what we looked like, he picked up an ear of corn off the ground to “call” his birds, who flew into his hand immediately.

Elsewhere, we met singers, we met dancers. We met teachers and students in a school; we met nurses who worked in a hospital just down the street from the school.

One of my favorite visits was the day we met a group of kids playing baseball in a Havana park. The chain link fences separating the stands from the field had long since been chewed up and torn apart; the dugouts looked like they’d been built and painted decades earlier.

The kids played with a joy I’ve seen my own little man play with when he and I play football in our back yard. Whenever I look at these photos, I wonder if any of these boys ever made it to the major leagues here in the U.S.:

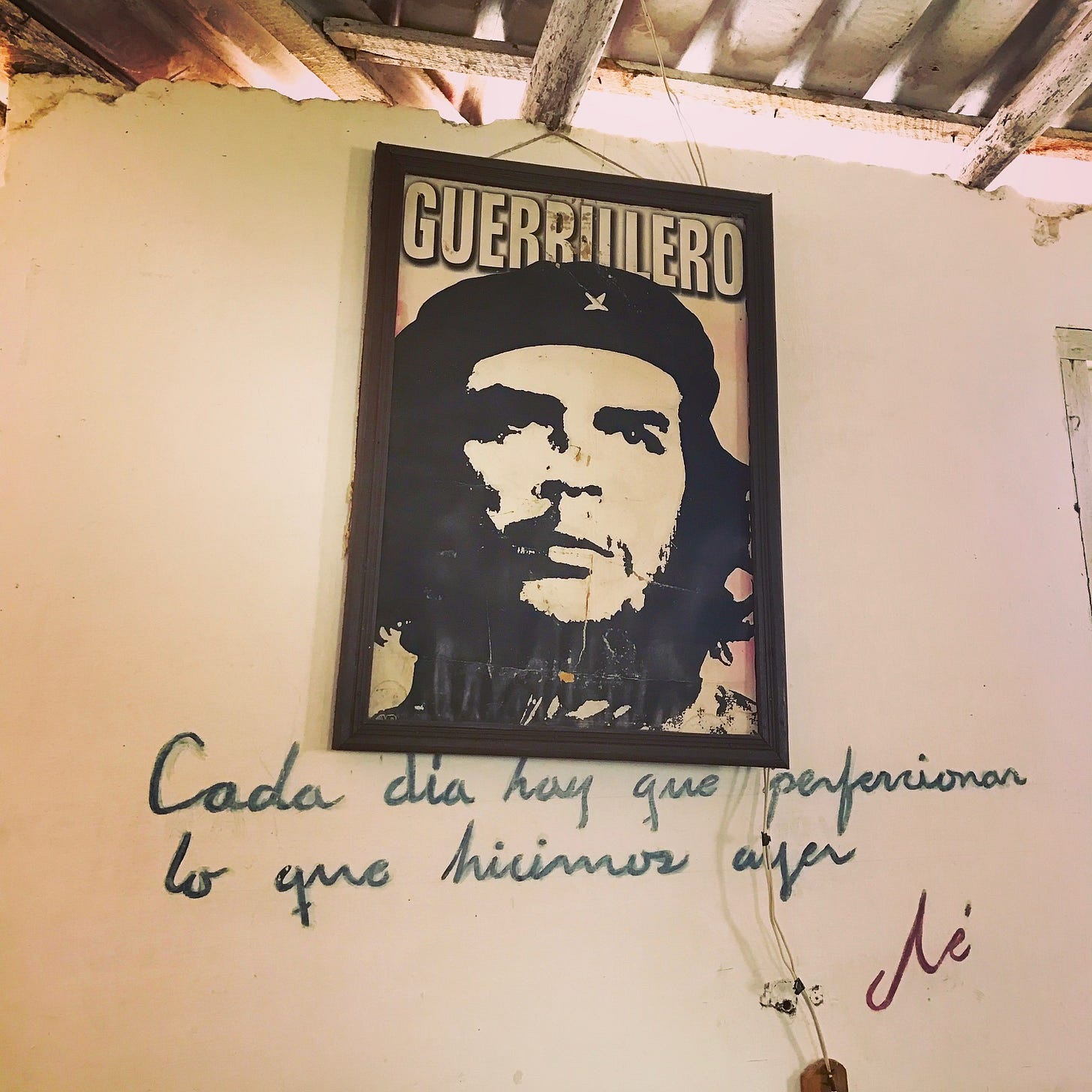

The most remarkable thing I found on the trip, though, was remarkable (to me, at least) because we saw it everywhere: photos, posters and illustrations of Cuba’s revolutionary leaders, be it Fidel or Raúl Castro, or Che Guevara.

Framed photos of Guevara were on the walls of many of the buildings we entered throughout the trip, in towns big and small; posters of both Castros were plastered on walls and buildings all around Havana. You couldn’t take a bus ride without seeing Castro’s face at least a few times around the city.

Their faces, and famous things they’d said or written, were present anywhere and everywhere people might find themselves in Havana, so often that you’d never forget them.

We also visited a plaza near the center of the city, where in his younger days Castro — he’d died the previous fall at age 90 — would assemble groups of thousands to stand and listen to hours-long speeches on a regular basis. (Attendance wasn’t exactly optional, we were told.)

To have the hand of the leader always on your shoulder — metaphorically, at least — no matter where you went, or what you did… it was such an alien thought to me, as an American. But there, it was inescapable.

Given all of that, and how suffocating it must be, it was perhaps surprising how many people we met who clearly were unbowed by it. They had found something in their lives — their job, their family, their neighborhood — that brought them joy and purpose.

Now of course it would be fair to say I’m just an American on a tourist visa; I only saw a glimpse of their lives, a tiny fraction of what life there is actually like. And that’s all true.

But I like to believe I caught a tiny bit of their hope, their resilience, their courage in the face of forces much larger than themselves — how they carried themselves, and how they still managed to find beauty in their world.

I hope to make it back someday, if for no other reason than Havana puts on a gorgeous marathon through its city streets every November — who knows, maybe I’ll make it?

In the meantime, I hope you have an amazing Sunday and get a great run in today. It’s in the teens here where I live in Georgia! As always, stay safe, stay warm, and keep me posted on how your running/life is going.

Your friend,

— Terrell

There are so many beautiful places in the world, but what really makes travel special is the people. It can be eye opening to see how others live and what makes them happy.

This really resonated with me, especially the contrast between political oppresion and people's everyday resilience. That detail about Castro's face being literally everywhere made me reconsider how differently we experince freedom. The tobacco farmer mocking cellphones with his corn "call" is such a perfect moment of human connection. Back when I traveled through Eastern Europe, I saw similar patterns: people finding joy despite systems designed to control them.